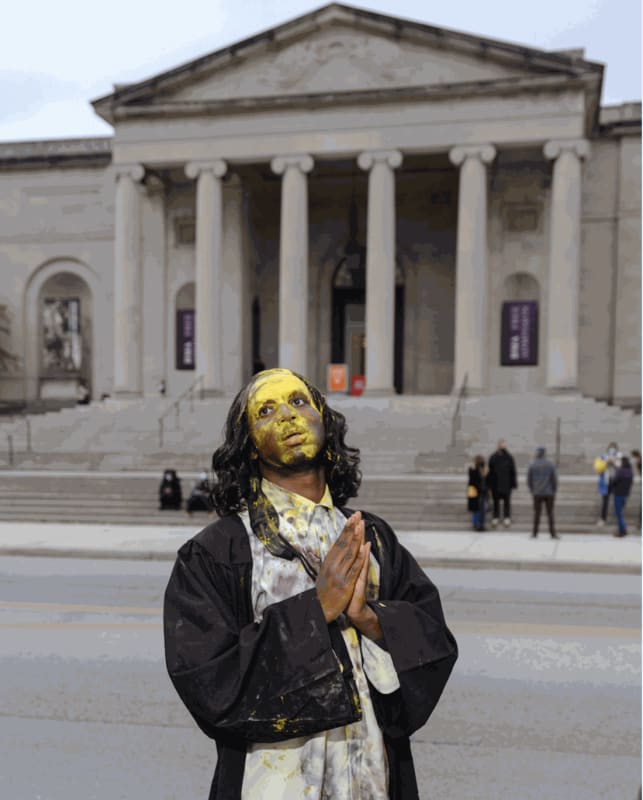

Monsieur Zohore, whose practice encompasses sculpture, painting, installation, performance, and video, often explores the complex intersections of levity and gravity. The artist’s work incorporates multifarious materials and objects as part of lively engagements with pop culture. Zohore is part of Pace’s ongoing online group exhibition Twenty-One Humors, which focuses on enactments of wry and dark humor in art and complements David Byrne’s in-person solo exhibition at the gallery’s New York space.

The following statements from Zohore, which have been edited and condensed, span Twenty-One Humors, the artist’s solo exhibition at the Washington, D.C. gallery von ammon co., self-awareness in art, and other topics.

I have two different bodies of work in Twenty-One Humors. There’s a sculpture in the show called Hurricane Becky, which is a standard oscillating fan that’s been outfitted with braids and beads to kind of mimic the cultural phenomenon of post vacation, middle school, white female teenagers coming back from a trip with these braids that we’ve all deemed now to be culturally appropriative. Exchanging the body of the human for this mechanical object that can take on a kind of humanoid gesture creates the comedy of that work. I love this series of sculptures—I’ve been making them for a while now, so I’m really excited to have one be seen on a global platform.

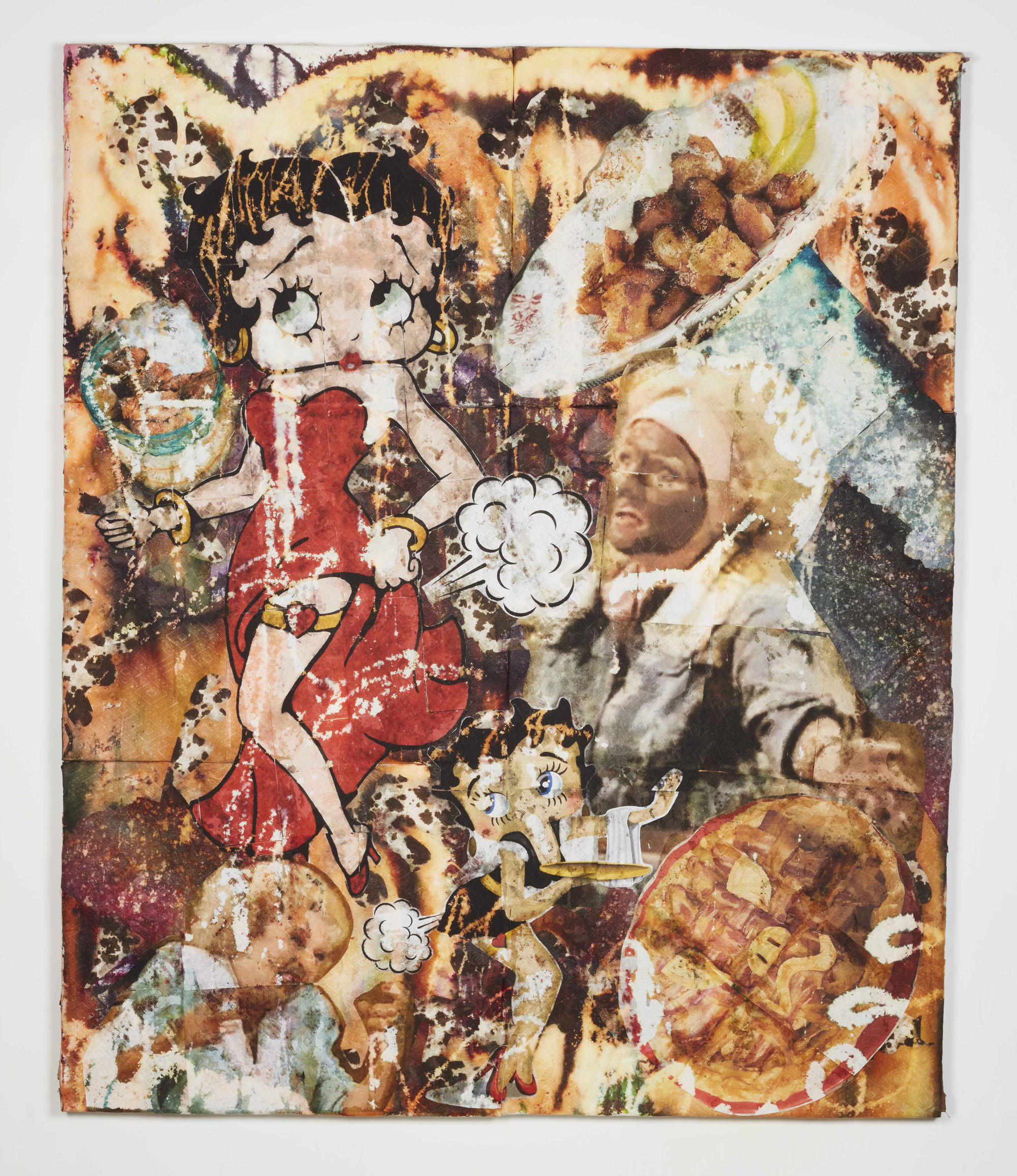

The other two works in the exhibition—Brown Betty and Animal Lover—are part of my paper towel project. These paper towel works masquerade as facsimiles of paintings that I make using Bounty paper towels, an inkjet printer, fabric dye, and bleach. I put these works through an archival bookbinding process to solidify them. I think of them as visual essays, and I usually combine some kind of art historical reference with a pop cultural subject. On the occasion of the death of Betty White, I thought it would be fitting to pay homage to her humor by mining her archive. So, the piece Brown Betty features a combination of Apple Brown Betty pies and Betty Boop farting on Betty White in that one scene that she was kind of in blackface. It’s not a commentary on that, it’s just allowing the audience to be outraged if they want to. Sometimes I think a work is funnier if it’s meaner, or if it pretends to be mean.

The other painting, Animal Lover, uses a scene from a film in which Betty White was in love with a gorilla. The image of Betty White being in love with a gorilla is masqueraded by a bunch of animal prints, and Betty White was famously an animal lover and an animal rights champion. The work is a funny, tongue in cheek homage to her passing.

Rethinking what the female figure looks like in painting is a really big discussion that we have been dealing with for a while now. The idea of a woman farting in a painting is funnier than her being naked. For me, it’s a much more fruitful and generous occupation for a figure to have inside of a space as opposed to the nude reclining or something like that.

I describe myself as a clown—that’s one of my artistic descriptors—and I’m really interested in the intersection of tragedy and comedy. How close can you get to one, and does that closeness help you get nearer to the other? A lot of my works tackle humor head-on. Humor is so exciting because it’s such a diffuser: I’m able to use it as a way of augmenting tragedy or minimizing it. In a certain sense, it’s a way of placating my audience into paying attention.

My work oscillates between nasty interrogations and desperate, sincere pleas. Right now, I have an exhibition at von ammon co., my gallery in Washington, D.C., called Les Éternels. It features two sets of reproductions Dragon Ball Z orbs that figure in the cartoon. In the Dragon Ball universe, the balls are made by this mythical dragon and our heroes are on a quest throughout the program trying to receive all seven of them. Once they have all the orbs, they’re granted a wish by the dragon. So, these become objects of desire and wish fulfillment, and those wishes are generally used to resurrect someone who’s passed away. I approached making the balls by memorializing each set to a specific person who has passed away. In this exhibition, there are two sets. A green orb set for Marvin Gaye, who was born in D.C. and is celebrated for his contributions of love and happiness and joy to the world. He was tragically murdered by his father. The other set of balls is for John Allen Muhammad, the D.C. sniper. He terrorized the community through his random acts of killing in the city in the early 2000s, when I was a child. Imbuing these whimsical and, in a sense, comedic orbs with an austere narrative is one way that my practice moves between those ideas of tragedy and humor.

I think visual art is a successful conduit for humor because art doesn’t have to be anything. It takes me back to the Magritte “This is Not a Pipe” painting. It’s not a pipe, it can’t be, and that’s why it’s funny. It doesn’t have the power to become the thing that it’s pretending to be. That kind of limit makes it inherently funny or uncanny.

For me, art has to be funny. There has to be something that doesn’t sit right with the viewer. I think humor comes from self-awareness, and that self-awareness is always what I’m looking for in a successful work of art. Works that are too delusional without being participatory in their delusion start to fall apart for me.

As told to Claire Selvin.