Originally inspired by Unite The Right, Sandy Williams IV’s monument candles are more relevant than ever today. Here’s what his was monuments can teach us about monumentalism. Hint: it’s a whole lot more than melting the dudes.

Sandy Williams IV has a new studio, courtesy of the University of Richmond, where he teaches. It’s painted white, with pipes running across the ceiling. “It’s probably one of the better studios I’ve ever had,” he said, a meek smile on his face as his eyes flitted across the room.

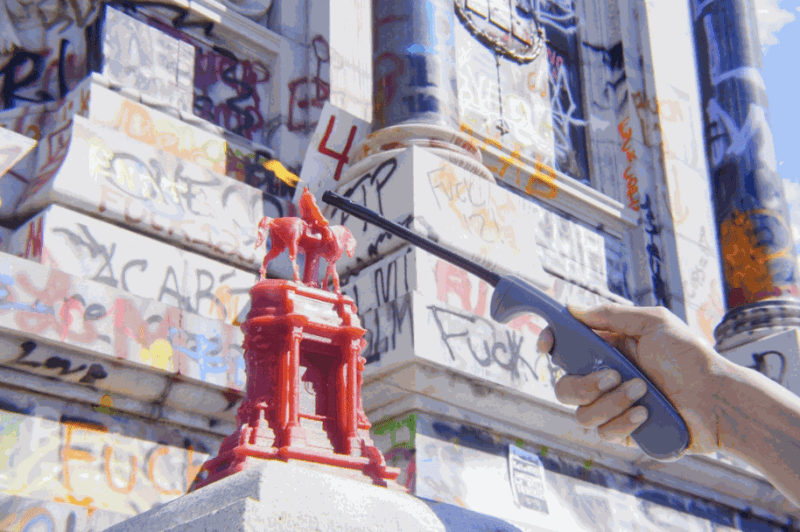

Williams’ shelves are stocked with rows of wax monument candles of different colors, each no more than a foot high. He picked up a silicone mold to show me the process, which involves casting a 3D print. It took him a minute to jiggle the statue free.

Williams never planned on becoming an artist, but his plans were thrown into disarray when he was 18. He’d been living the dream — high school prom court, involved in student government, and talented soccer player. His plan was to be an orthodontist, because it paid well. But then he was diagnosed with cancer, and all of that went away. He started to spend most days of the week in the hospital.

“Chemo is a trip. I went from being a normal high-schooler — homecoming court, prom, whatever — to just doing nothing but chemo,” he said. “After chemo I was like, well, how important is that paycheck if I’m not really doing something that matters to me?”

Williams’ journey as a conceptual artist began at the tail end of his chemotherapy treatment in college at the University of Virginia. He took his first art class, an observational drawing class, to fulfill a credit requirement for school.

“It really became this supportive community that I was missing,” said Williams, who was at the time used to 300-person Biology lectures. “I went from that situation to meeting daily with this professor who knew my name and knew my story, and was really invested in helping me get better.”

His early, more introspective work involved sitting in front of a camera for hours as the white balance struggled to even out his complexion. Now, in his words, “the lens has turned the other way.” His wax monuments are one of several projects meant to start a conversation about people on pedestals, and are years in the making. It all began with the Unite the Right Rally in 2017.

At the time, Williams was living in Charlottesville, and preparing to move away. “I was on my way to work actually – I was working as a waiter – and this truck of men with Confederate and Nazi flags drove by me and all threw Nazi salutes at me,” he said. “I was like, ‘I gotta get out of here.’” The right-wing rally took place at the Lee statue in Charlottesville, a familiar spot to Williams and his friends. Soon afterward, he departed for Richmond with monuments on the mind.

In his first year as a Sculpture grad student at VCUarts, the air was just right for discussion. “We were doing tons of readings about monuments throughout history, what happened in South Africa and apartheid and what they did with their monuments, and so I decided to keep pushing it,” Williams said.

It’s a weird feeling to look at tiny versions of these grandiose objects. In an interview with the Reynolds Gallery, Williams said that his monument candles are an opportunity to meditate on what the symbolism of the actual monument means to us. Or — for those who’ve contemplated enough and are ready to see the statue gone — to feel the relief of regeneration.

To make them, Williams starts with a 3D scan. Scans of monuments are out there; Williams explains that there are a couple of different foundations around Richmond that have been doing archival scanning of monuments. However, he said, “sometimes they’re not so interested in sharing them,” at which point he has to turn to the internet, or even do the scans himself.

Once he has a scan, he uses the materials available to him at VCUarts and the University of Richmond to make a 3D print, which he then casts in a mold. When the mold is ready, he pours wax into the negative space to make a candle.

The first candle Williams ever made was the easy-to-scan Jefferson monument, as seen on the UVA campus. Then, taking a slight departure from Confederate generals, he made a Lincoln. This choice, he explained, was to expand the depths of his message. “Especially within the setting of an art gallery, it was a very left-thinking conversation, when my intention was more radical than that. It wasn’t just about ‘melt the racist monuments.’”

Williams felt that the typical art-world conversation about monuments needed to be widened in scope. “The conversation was getting simplified or flattened,” he said. “It was a missed opportunity to have real conversations about changing the infrastructure of the system, not just who sits on the pedestal, but really why we’re building these giant pedestals to people who aren’t here anymore when there’s so many people that need that space.”

When it comes to the subject of memorialization, Williams’ practice isn’t limited to his monument candles. One of the ways in which he explored this idea was in his cleaning of the Statue of Liberty monument in Chimborazo Park earlier this year. Like many of Williams’ pieces, it had a simple exterior that contained a much more complex project.

“It wasn’t even a Confederate statue. It was this random Statue of Liberty that was put there by the Boy Scouts of the Robert E. Lee [Council] in the fifties, during segregation, in Chimborazo Park, which is this memorial to the largest Confederate hospital during the Civil War,” he said. “Right after the Civil War, it was a freedman community. But there’s not a single sign commemorating that activity, right? All of the signs are just about the importance of the space to the Confederacy, but it totally washes away the history of the fact that after the Civil War, hundreds of freed slaves lived there before the city evicted them. The city was doing things like buying people one-way tickets to Chicago and Philadelphia, just to push those people out of the city.”

His idea was to invite people to, in a way, introduce themselves to the statue. Touch it, change it, care for it. In doing so, they would “activate” the statue. This process can be empowering to those who feel helpless against tradition, and it provides an opportunity to reflect on what the statue means to us while performing a public service. At least, that’s the hope.

There were complaints. Two or three times a day, a voice called up to Williams from the sidewalk, worried he might damage its natural patina. “Mind you, I got permission from the city,” he said. “I got permission from the police department, I got permission from parks and rec, so I was very much allowed to be doing what I was doing.”

Nonetheless, he went ahead and explained what he was doing to those who stopped and questioned it. “I still felt it was important to have those conversations,” he said. “And now, in what they are considering a crisis situation, they’re like, ‘All right, we’ll just take [the Confederate statues] down.”

While Williams supports the removal of the monuments, he doesn’t want the complexity of their impact to be overlooked.

“It’s so much deeper than just the statue. It’s a thirty-foot symbol of the racial inequality that’s existed in this country since forever,” he said. “Lee is just the biggest symbol. It’s in murals all over the place; it’s in pictures in restaurants. The more I worked on it, the more I started to notice — it’s just everywhere. It’s become such a representation of what Richmond is. And I think a lot of people are tired of being represented in such a way.”

Making monuments is only half the battle, though. To take full advantage of their artistic potential, Williams likes to melt his wax monuments in front of their originals. Considering it’s illegal to perform any kind of demonstration in front of monuments, this has been a bit of an obstacle for Williams at times. When he attempted to melt his Lincoln statue at Washington DC’s Lincoln memorial, Williams approached the guard. “He was very nice about it. He was like, ‘Somebody’s gonna call me in about 15 minutes to say that you’re doing something, and after that I’ll give you ten more minutes to finish your project before I tell you you need to leave.’ So I was like. ‘Okay, right on — we’ve got 30 minutes.’”

In Richmond these days, though, such complicated negotiations may no longer be necessary in the fight to deconstruct such symbols. “Now when you see people setting up PA systems on the Lee, and so many different voices get projected around the area, that’s totally the conversation that I was interested in pushing, that all of a sudden is very much the reality of the situation,” he said. “It went from being like, ‘Ah how do you push these conversations?’ to… ‘I don’t even need to do that work anymore, it’s just happening.’”

Seeing this change occur means a lot to Williams. “Just thinking about the ways in which those spaces are so inaccessible… unemancipated is another word I’ve been using,” he said. “When you look at what the Lee monument had going for it before the uprising started… and now, the life that exists around it, the activity. I think that really encapsulates what this project meant for me when I started it in 2017.”

Back when Williams started making art in college, his professors made it very clear that fine art is not a lucrative path. They told him he’d spend ten years a student, ten years as an emerging artist, twenty years as an established artist, and then maybe become famous.

“And I was like, ‘Jeez, I should’ve gone to med school! It’d only be 8 years,” he said. “But it works out in its own ways, even if it’s not going to be selling your work for millions of dollars. There’s so much else you can get out of it. Monetarily, it’s definitely a struggle… I get rejected from things I don’t even remember applying to, just because I’m applying so often to things. Whatever it is, I’m throwing my name in the hat. It’s just part of the grind, part of the practice.”

Williams moves with patience. At one point, when I asked if he had enough time to finish the interview, he said he had plenty. He was just planning on working in the studio that day.

“Making it was never a concern of mine. If I die next year, I will have at least left marks of my being,” he said. “I think building this foundation on my work being important to me, first and foremost, before any outside recognition, that’s how I’ve been able to persist for so long. Even with this candle project.”

Clearly, his continued work has paid off. When he got started, nobody wanted to buy a candle for $20. Now, he’s working with 1708 Gallery to raise thousands of dollars for the Jackson Ward Youth Peace Team through sales of his wax monuments. As of right now, all of them are sold out.

You can check out the full collection of Sandy Williams IV’s wax monuments on his website.