“History has a way of intruding upon the present, and perhaps those who read it will have clearer understanding of what the American Indian is, by knowing what he was.”

- Dee Brown, Bury My Heart At Wounded Knee

The American West. What images does it conjure for you? If you’ve read traditional American history that covers European man’s foray into the dark, tough and – ultimately – ripe-for-the-picking forested lands of North America, it may sound heroic. After all, many, if not most, Christopher Columbus-inspired pioneers from the 15th to the 19th century fled persecution in the Old Country, or a part of America they didn’t like, for a more fertile or remote area in these lands to cut a fresh swath of acreage with new rules to call their own, ensuring safety, serenity, a bit of bounty and an incredible distance from the taxman. But we eventually learned from thorough revisionist history that it didn’t quite go that way. Indigenous North Americans totaling nearly a hundred million lived in virtually all regions throughout the land, creating complex, dense village centers that functioned for thousands of years prior to infiltration and displacement by the brutal, entitled and ultimately devastating settler population.

When time passes by, history changes, as do our mythologies surrounding that history and the imagery that defines – or even defies – it. The new comprehensive group exhibition, Real Wild now on view at Palo Gallery through November 20th, lives up to its namesake and reviews the tropes, tips, and lessons we might want to heed in order to stay on top of our often-dropped obligations as sympathetic humans. Over seventy works of art presented by nearly three dozen artists – from Andy Warhol and Beverly Buchanan to Edgar Heap of Birds and George Grosz – show a staggering variety of approaches to making art with American West themes and applicable plumb subjects – cowboys, “Indians”, equine life, log cabins, and open warfare – that raise our initial attention before we see the twists in each work that reveals our previous need to hide heinous acts of the past perpetuated into the present.

While most of the work was created within the last few decades, a notable grouping of ten hand-rendered “Ledger Book Drawings” created by Indigenous warrior-artists and collected by white settlers, give us an inside glimpse into the male perspective on Indigenous life. A Sheridan Ledger Book drawing from 1885, without attribution, depicts two male warriors on horseback courting a young Indigenous woman who pauses her collection of water to interact with the men. It reminds us of simple, but utterly sincere, no-perspective color drawings of perhaps today’s school children, but that tackle adult subject matter pertinent to Indigenous people. Other drawings in the suite show white soldiers in blue flannel uniform firing long arms upon subjects – presumably Indigenous people – out of the frame. Another drawing, Vincent Price Ledger Book (page 23) Southern Cheyenne Central Plains, reveals what looks like forbidden love – a white soldier with open arms approaches an Indigenous woman on horseback also with open arms rushing towards one another.

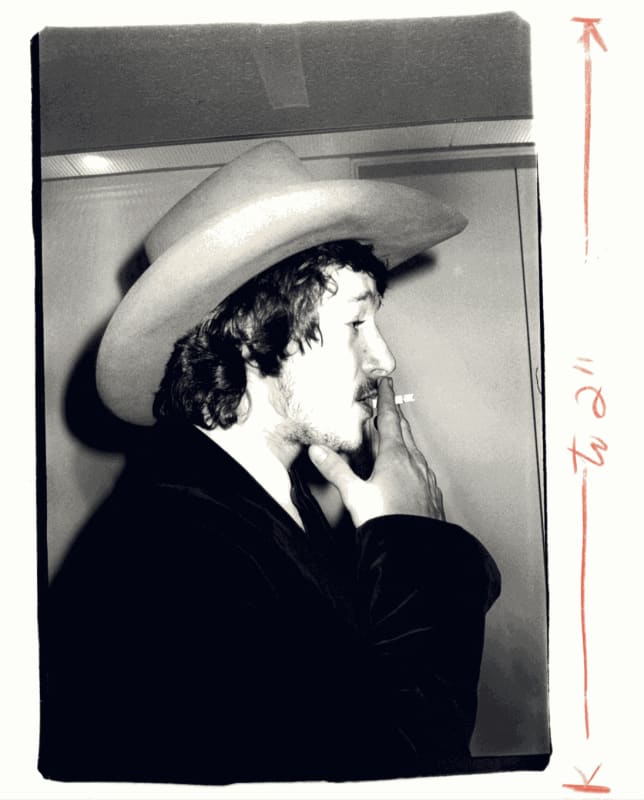

Fast forward about a hundred years to the early 1970s and Andy Warhol, a child of the 20s and 30s heroic ideal of the Western Man as writ by novelists like Zane Grey, and we see a simple elegant 8”x10” black and white photo, Man in a Cowboy Hat Smoking, snapped by Warhol. Its shows a guy doing exactly as the title indicates in profile. It could be a Warhol Factory guest, a street hustler, or a real cowboy – who knows – but its informal depiction that almost appears as a mug shot – strips the heroism away and leaves us wondering what the “to 2”” written in red ink means along the side of the photo. Perhaps it’s just an indication of what it might become - a small, reproduced screen print in the sea of simulated images subsumed by Warhol and the masses.

A series of text works by contemporary Cheyenne and Arapaho Nation artist, activist and teacher Edgar Heap of Birds, such as Native Host Panels: Salt Lake City from 2012 and Native Host Panels: California from 2013 made of Mylar on metal sheeting, show viewers a contemporary “host” region written backwards followed by “Today Your Host is Nuche” or “Today Your Host is Pavu’nga” and any other original Indigenous land names that indicated the actual parcels of land, which made up what white settlers strung together to later declare a now-common state name and, often, a larger collection of land. Of course, these works seek to let viewers know the origins of Indigenous nations and the retrogressive acts of those who supplanted real First Peoples that populated those lands and made them thrive.

Beverly Buchanan’s iconic, rough-hewn, color-saturated, oil stick drawings of shacks – simple dwellings of the downtrodden and destitute – upend the bleak outlook that the subject may imply, and as the artist indicated, would instead “evoke the warmth and happiness that can be found even in the meanest dwelling, representing the faith and caring that is not reserved for privileged classes." These are surprising little gems in the show.

In a much more dramatic manner, through carefully staged tableaux color photography of modeled sculptural miniatures, artist Robert Ross’ large work, Untitled from 2022, depicts a significant car accident of a 1960s Ford Thunderbird crashed into a neon “Western Motel” sign. Three figures, one pointing a pistol at another holding a dead woman – who just escaped the wreck – reveal a lost cause, a lost era, and the death of the dream of the West as an escape plan. It feels like a scene from a classic 50s noir feature film, but remains somehow more matter-of-fact, giving us the wide, step-back view of the unfolding mystery, asking us to review what happened instead of throwing us directly into the fire.

Overall, Real Wild presents a solid show of works with only a few exceptions that utilize western iconography almost incidentally or as a camp retreat from some of the pressing matters perennially at hand. But then again, some of us live in the fantasy world that we recreate for solace and laughs, while others exhume the haunted, buried past to hopefully make the future brighter.

This timely and pertinent exhibition brings necessary, storied history lessons, rich folklore, and presents artful views about American West iconography that clearly carry over into today’s culture – both the effects of violence and colonization, as well as many numerous modes of fighting for freedom, personal identity, and a very human desire to ultimately spread our wings. WM