“Ha,” I blurted, “So pop was a blow job in a gay bar.” I think Jeremy actually blushed.

“I think pop was a bit more ambiguous,” Jeremy said. “The same way Andy Warhol was sexually ambiguous, if not asexual. In fact, Laing wrote a lot about Warhol. He describes his bland non-sequiturs, such as ‘I like boring things’ or ‘machines have less problems, I’d like to be a machine, wouldn’t you?’”

Jeremy then took out a spiral pad filled with scribblings. It looked like a fifth grader’s notebook, judging by the words Algebra 2 written on its cover with a Sharpie. Another quote of Laing speaking about another pop painter who was not gay, James Rosenquist, read: “I met Jim Rosenquist first. He is a Scandinavian from the Middle West. Fair-skinned and blond-haired, stocky and strongly built, he gave the impression that he could easily be at home on a tractor in some vast grain prairie … Jim’s technique owes everything to the advertising billboards which he used to paint for a living.” He then describes the “painted foam and a misty chill of condensed moisture sliding down the side of a glass of Heineken 40 feet high.”

“Another cock,” I shamelessly offered.

A few minutes later, our jet made a smooth landing in London, and I was standing in the clogged aisle unlatching the overhead storage bin responding to Jeremy’s questions about whether I had any idea which gate his connecting flight to Glasgow would be departing from.

“What am I your babysitter?” I asked, grinning. Guys Jeremy’s age, who consume that much alcohol and Adderall on international flights, usually don’t have a clue how to get to their connecting flights. Without their wives, they really can’t do anything, or get anywhere—which leaves them quite vulnerable to Zoomers like me. Not to brag, but in college, if the teacher was a frumpy white man over 30, I knew I could get an A in the class without ever attending the class. All I had to do was write the teacher a thoughtful email at the end of the semester explaining my traumas. Where should I start?

“Where are we going next?” I asked, tossing him his bag, which rattled with pills. I slung my backpack over my shoulder and gave him my best selfie face as he responded “Glasgow.”

After finagling with the agents at the British Airways ticket counter and managing to get new seating assignments, Jeremy and I were seated side by side on the short flight to Glasgow. Even before we had taxied out to the runway, Jeremy flagged down the flight attendant. “How ’bout a cold beer?” Picturing the Rosenquist, I added, “Can you make that two?”

Soon the plane landed and Jeremy reached for his phone, dialed a number, and spoke to whoever we were traveling to meet. “Hi. Is this Fucker?” I heard him ask, before realizing he was attempting to pronounce the Scottish name, Farquhar, which is often wrongly pronounced “Far-Quar” but is in fact closer to being pronounced “Far-Kur,” or just “Fucker.”

“So I don’t think I mentioned that I will NOT be arriving alone.” There was a short pause and Jeremy looked at me while speaking into the phone. “Excellent! I’m so glad. So we will be on the next express train to Inverness. You can expect us around dinner time.” Jeremy held his hand over the phone and whispered to me, “Farquhar wants to know if we eat pheasant? Do we eat pheasant?”

“Yes, we both love pheasant!”

I watched Jeremy’s eyebrows grow intense as he listened. “No, my friend will not need her own room or bed. That’s no problem at all.” He didn’t even bother to look back at me, which struck me as kind of bold.

Anyway, we hustled by taxi to the station and hopped on the last train headed to Inverness. Again, not to brag, but it was only my Gen-Z smartphone skills that allowed me to purchase our tickets online and flash a barcode to the conductor just seconds before the train departed. Had it not been for me, Jeremy would have been stranded in Glasgow all night, probably blowing his earnings on whiskey in a five-star hotel bar.

Pretty soon we were well situated on the train, sitting across from one another at a little white table and staring out the window at the expansive mountain terrain and unpredictable cloud formations that occasionally locked together into ordered compositions of grays, pinks, purples, and oranges, then quickly evaporated into mist. We watched herds of crofting sheep drifting across green hills, clean of even a single tree, as our train rocketed toward our destination in the Black Lake region at the northern tip of Inverness.

I watched Jeremy dig through his bag, fiddle with the lid of one of his medications, spill out another blue pill, and this time use his credit card to crush it into a powder. He then formed it into a thin light blue line, rolled up a dollar bill, snorted half the powder, and handed me the bill. I inhaled the rest, taking my first-ever blast of pharmacy-grade speed, which I immediately knew was far better than any of the bad cocaine my friends and I tended to use as our “alcohol stabilizer.”

I grabbed for the book Kinkell: The Reconstruction of a Scottish Castleby Gerald Laing, and quickly became intrigued by still another aspect of the Gerald Laing experience. The man was an excellent writer. From page one, I just couldn’t put it down, until I came upon a word I didn’t know.

“What’s a ‘castillated dwelling?’” I asked Jeremy.

“A castle,” he replied, keeping his face basically glued to the window.

I read how Laing, “was able to obtain a ruined castle and begin work on it” with his “new bride” Galina—who was, back then, working in the city for this famous fashion photographer, Bert Stern, who had shot Marylin Monroe (in a gauzy yellow see-through top) and other big celebrities. It was Bert Stern who had given Galina a dove—like, an actual dove—to take home with her after they’d used it on a Dove Soap photoshoot. According to the book, using chance, Galina and Laing set the dove down on top of a huge map of Scotland’s upper highlands and decided that wherever the dove laid its first dropping would be the spot on the map where the romantic couple would be destined to find their ruined castle.

“These guys were pretty adventurous,” I said, but Jeremy wasn’t paying attention. I kept reading and came across a second amazing story of chance—about the moment that a hub cap fell off their tire and bounced across the pavement, right to the little gravel road that led to Kinkell.

“Listen to this,” I said, reading the next paragraph out loud to Jeremy about the day Gerald and Galina bought Kinkell off this old farmer named Angus Macdonald. “Whisky followed whisky; Angus became more voluble; the shadows grew longer and we grew more impatient to see the building. Finally we suggested that if we did not go soon it would be too dark to see anything.”

“And what did they find?”

“Says here: ‘the overall impression was of solid walls, but collapsing roofs and floors … The building was well on the way to returning to nature …’”

“I guess we will soon see for ourselves.”

“Well that’s where we’re going!”

“We’re going to Kinkell?!”

“Actually it’s pronounced Kin-kell! With emphasis on the second syllable. But yes, that is where we are going.”

“No fucking way! We’re going to stay the night in a castle?”

“No, even better—in the guest house right next to the castle.” I looked down at my belly and imagined myself pregnant, just like Nicholas Cage’s wife, who was not just one, or two, but THREE decades younger than her husband.

“He can be very funny,” I said to Jeremy. “Listen to this part about when he was preparing to pose in a photograph with a bunch of hot British artists—Allen Jones, Richard Smith, and David Hockney—for this article about the mini-British Invasion: ‘I wore a new lightweight Italian suit which I had bought just before leaving London—one that, worn with the requisite aviator sun glasses and white leather shoes, projected the sort of image deemed appropriate: cool, efficient and full of a sang-froid which was brutally upset when my trouser seam split clear around the seat from stem to stern. The suit was very inexpensive. I kept my back to the wall and sat down for the photograph. I do not think that you could know by looking at it what had just occurred.’”

Our train pulled into Inverness station. Jeremy and I stepped out onto the platform, and were greeted very warmly by one of Gerald’s two sons. It was the younger one, named Sam. We slid into the van and I introduced myself from the back seat, looking at Sam through the rear view mirror. “I’ve never driven on the wrong side of the road,” I said, trying my hardest not to seem too much like a tagalong.

“Welcome to the United Kingdom,” Sam replied in a soft voice with a beautiful Scottish accent. Soon we pulled into the driveway, past a stone wall, and there it was, Kinkell, the medieval castle pictured on the cover of the book I had been reading, surrounded by fields covered with rolled bales of barley ready to be hauled off, and a mountain range off in the distance. The sun was going down, so there was a golden, rosy glow on everything.

We walked across the yard approaching the castle and passed a very commanding jet-black metal sculpture perfectly positioned (by crane, supposedly) on the lawn about 30 feet away from Kinkell—in perfect dialogue with its white, sleek vertical stature. Jeremy pulled his long, frizzy, gray hair back into a bun and circled the 15-foot-tall artwork, which was clearly a cubistic head of a woman.

“It’s my mom, Galina,” offered Sam.

Jeremy kept circling the piece, apparently surprised by its contours and unexpected, scooped-away voids.

Just then Farquhar came out of the house and made a beeline toward us. He leaned in, gave me a soft kiss on the cheek and introduced himself to Jeremy with a very firm handshake. I immediately pulled out my phone and took a selfie in front of Galina. Then I had the good sense to ask Sam and Farquhar to pose in front of the sculpture with the castle in the distance. I was proud to have made myself of use, in a Gen-Z, iPhone-ish sort of way.

Jeremy compared the work to “Darth Vader.” He then compared the artwork to a famous futurist work called The Dark Horse, by an artist named Villon-Duchamp.

Farquhar stood with his arms crossed, as though he were admiring his own masterpiece as much as his father’s. “I wish Dad were still alive to see it produced on such a commanding scale. It’s never been done this large.” He gave it a single knock, creating a dull ring. “It’s hollow, and not a single weld shows. I think there are over 20 casted parts to it.”

“You made it yourself?” I asked.

“No, no, no. Now the foundry employs close to 15 men. We’re called Black Isle Bronze. We do projects all over the place. I actually took what I learned about casting bronze from my dad, who basically was self-taught, and developed a bit more expertise.”

“She really fits nicely with the castle,” said Jeremy. “Her face is fortified, as if she’s going into a medieval jousting contest. It’s not just a cheekbone.”

I followed the three men in through a very thick, solid oak castle door and suddenly I was surprised to find myself in a cozy kitchen, greeted by a beautiful and charming woman with a very friendly smile. It was Farquhar’s wife, Jill, and she was already preparing dinner. She joked that she was working very hard to remove all the lead shot from the numerous pheasants that Farquhar had killed in a hunting expedition over the weekend.

“Smells great,” said Jeremy, making some crack about “expecting haggis,” which I quickly googled, discovering a traditional Scottish dish that is said to be “an acquired taste.” Farquhar then offered to lead us on a tour of Kinkell, which began on the thick, stone, spiral steps inside the fortified turret. All I could think was that it was the first and possibly the last time I would ever step foot in a home constructed in the 16th century. Farquhar (or Silver Fox No. 2) stopped to explain how, back in medieval times, any Viking intruder would be forced to carry his sword in his left (weak) hand, in order to have enough overhead space to move up the steps, giving the man defending his home the so-called “upper hand.” Sam (Silver Fox No. 3) then squatted down and pointed to a tiny hole in one of the very thick, angled stone steps.

“See that little hole?” he asked.

“Oh! I read about it in the book,” I blurted out, a bit too much like a middle schooler trying to impress her teacher. “The owner of the house would use that hole to peek down and see whatever intruder might be trying to invade the castle.”

“Indeed,” said Sam, as we entered a room on the second floor. Farquhar lit a fire in the wood-burning stove, and Sam went in search of a bottle of whiskey and four glasses. We toasted to Gerald Laing and moved on to Gerald’s studio.

This is where Jeremy took an interest in Gerald’s record collection, lined up on a shelf under his vintage-looking stereo system. He blew some dust off an album cover and flashed it to me. It read Axis, Bold as Love by Hendrix. Its cover art is borrowed from a Hindu image of the various forms of Vishnu—what a rock journalist once described as “a lot of freaky looking Indian cats and gods, sages and one guy with an elephant’s trunk for a nose or something!”

Jeremy then asked Farquhar if he didn’t mind putting it on. Sam splashed a second bolt of whiskey in each of our glasses, and on came the crackling sound of this old record from the ’60s, and a song called “Castles Made of Sand.” Jeremy hushed us all and asked our hosts to turn it up, as he threw yet another blue Adderall into his mouth and chased it with a gulp of whiskey. I grabbed the album and began to read the lyrics, as the three silver foxes sang along with Jimi in unison.

Down the street, you can hear her scream, “you a disgrace”

As she slams the door in his drunken face

And now he stands outside

And all the neighbors start to gossip and drool …

He cries “Oh girl, you must be mad

What happened to the sweet love you and me had?”

Against the door he leans and starts a scene

And his tears fall and burn the garden green …

And so castles made of sand

After the word “eventually,” Jeremy sort of rolled back his eyes in a kind of ecstatic moment, listening intensely as the room filled with a guitar solo, which, he somewhat obnoxiously pointed out, was recorded backwards causing it to pluck and resonate a little more like a Sitar or a Hindu harmonium.

After the pheasant dinner, exquisitely prepared by Jill and cleansed of lead, we climbed the steps back to the second floor, splashed our glasses again with whiskey, and sat around a table looking through an old photo album from Gerald and Galina’s glory days in New York, and then in Kinkell, which was seen in many stages of renovation. Both Farquhar and Sam also appeared in many of the pictures at different ages, as did visitors from New York, like their closest friend and art dealer, Michael Findlay, who is dressed audaciously, in one snapshot, in a tartan plaid kilt held up with a leather belt ornamented by a big fat Texan buckle.

“Gerald and Galina were real contenders,” Jeremy said, commenting on a picture of the couple together with Roy Lichtenstein at some fancy party. And then another where they are seen with Warhol, Gerard Malanga, and the famous drag queen Candy Darling.

“My mom, Galina, actually had lunch with Andy only a few hours before he was shot by Valerie Solanas,” Farquhar said.

We then admired a postcard sent via airmail from New York City to Inverness from Robert Indiana, dated 1979. The funny thing was that the four 8-cent stamps were Robert Indiana’s actual U.S. postal stamp, picturing, naturally, the ubiquitous “LOVE” (or as we now know, the love cock).

But the most fabulous image of them all was one gorgeous black-and-white studio shot of Gerald and Galina taken by the Jack Mitchell. The very hip couple is seen entirely nude, embracing. The image shows them from the side, so that their private parts are mostly hidden. Jeremy didn’t actually know who Jack Mitchell was, until he discreetly typed the name into my phone and discovered a very iconic black-and-white portrait of John and Yoko, and then many others of airborne Alvin Ailey dancers.

“So how is it possible,” I asked, kind of taking over for Jeremy as lead journalist, “that Gerald Laing is not a household name?”

Both sons got very serious, almost grave, and took turns explaining a few facts. “It’s very complicated,” Sam almost whispered, as if the ghost of his father might overhear. “They were tired of playing the game. People like Robert Indiana once told my dad, ‘You must be seen everywhere.’ And that was the way it was. And they got tired of being seen everywhere!”

I just nodded, knowing if I said nothing, I was about to learn more.

Farquhar continued. “My dad and mom’s decision to leave New York when he was at the peak of his career may not have been the best choice. Because his market pretty much dried up within a few years. Dad refused to stay with one style, the way Roy did, sticking rigidly to those same Ben-Day dots. Also my dad’s gallerist, Feigen, decided to focus on the secondary market, and he kind of dropped his young talent and liquidated his contemporary art, rather cruelly selling a huge number of my dad’s early paintings at auction for nearly give-away prices.”

“So you’re saying that Feigen maliciously hurt your dad’s career?” Jeremy asked. “Because evidently, certain critics, like Barbara Rose, had written pretty scathing reviews of one of his shows, claiming that his ideas were ‘received,’ or in other words, derivative of other pop artists. Rose also said Laing’s work ‘lacked content to an astonishing degree.’ Remarks like that, in print, certainly couldn’t have helped.”

I just had to cut in. I was no art scholar, but I just couldn’t hold back. “Maybe she failed to see how interesting your dad’s subjects were.” I had the stage. “He really seemed to understand the adrenaline and the exhilaration of consumerism, not merely products like Campbell’s soup cans on the supermarket shelf.”

Sam, Farquhar and Jeremy were silent.

It was, like, my moment. “On the plane over, I read one quote by your dad …” I brought it up on my phone, as I had snapped a picture of the text earlier on the train. “Even the dealers would slip away from their own galleries in order to appear, however briefly …” I said the word “popular” in my head and kept reading how he described the remarkable turnout to his first show that included Leo Castelli and Roy Lichtenstein, everyone who was anyone. “Andy Warhol, Jim Rosenquist, Tom Wesselman, Barnett Newman, Mark Rothko and, of course, Robert Indiana—came to my first opening.”

“So, bold as love,” Jeremy said, “off they went to try to do something really romantic!—instead of settling for a life of slavery to the New York art world.”

We said our goodnights, confirming that indeed, we would love to meet them in the kitchen at 9 a.m. for a bacon and egg breakfast. Farquhar handed Jeremy what remained of the bottle of whiskey and encouraged us to polish it off back at the guest house. We carefully made our way down the spiral steps commenting that we were feeling lucky not to be carrying swords. And we walked out into the very dark night. No moon or stars were in sight. The fog had rolled in like a velvet curtain over the deep black horizon.

Back at the guest house, Jeremy popped an Ambien and ran himself a bath, while I got out of my clothes and slipped under the cool, crisp, starched, four-star, 100% cotton sheets. I took out my laptop and began to peck away at my keys, writing as fast as I could possibly move my fingers.

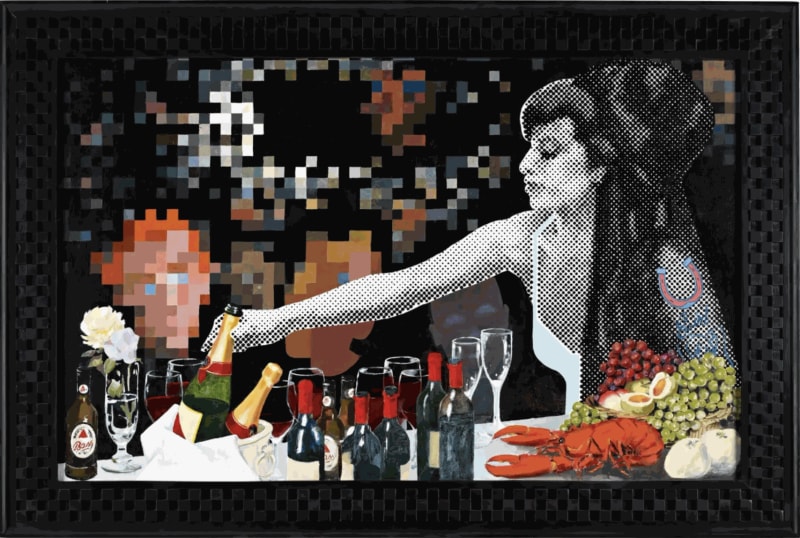

Emotions started pouring out of me about the tragedy of Amy Winehouse as I tried to describe one of Laing’s painful last paintings of her copied from a clipped newsprint cover of the Daily Mirror dated Friday, Nov. 9, 2007, with a headline reading “Amy’s man is cuffed and off to cells.” The painting was almost entirely black and white with its diagonal rays of half-tone dots and solid saturated flat shapes. It captured the frozen moment Amy clutches her boyfriend with bare hands holding on to the naked flesh of his face desperately kissing him goodbye. Our inquiring eyes then slip across the young man’s black tee down his white thin arms to his hands which are held in police cuffs behind his back. It had that French new wave aesthetic, or perhaps it was even more breathless—like the ‘80s film Jeremy had compared it to by John Lurie, Stranger than Paradise, with the unforgettable song he played for me by a guy named Screamin’ Jay Hawkins, “I Put a Spell on You.”

The painting’s title once again required Google: It was quite biblical actually, “Gethsemane,” which, according to Wikipedia refers to the olive grove in Jerusalem where Jesus lay in “agony” (was he suffering from withdrawal?) the night before being escorted away, nailed to a cross, and left to just hang there.

Who in Laing’s allegorical painting, I wondered, was playing the part of Jesus? Amy or her ne’er-do-well boyfriend? And would Amy be saved by the grace of God who presumably had called the cops to come and drag away the evil druggy enabler and punish him for all our druggy sins? Was Amy being depicted as a martyr, on the verge of soul sacrifice. Or was she finally being set free to sing the gospel?

As I wrote, I arrived at the conclusion that Winehouse’s problems ran deeper than her bad-seed boyfriend, with his class A crack and her infamous father who was also her worst exploiter. Amy’s downward spiral was written into her every fiber—her perfect Warholian car crash moment was coming head on in slow motion from the first time she ever stepped out on stage. It was the drug of celebrity that failed her, the spot light that spoiled her rotten.

I took another swig and went searching on YouTube and discovered a handheld cellphone video poorly shot of Amy’s last performance before her death from alcohol poisoning on July 23, 2011, at the age of 27, when she joined the 27 Club (Janis Joplin, Brian Jones, Jimi Hendrix, Jim Morrison, Kurt Cobain …). In a very poorly attended venue, Amy is caught out on stage trying to sing, while her sturdy backing band stands around indifferently letting her unravel. She no longer seems to know the words to her songs or how to sing them. She can no longer find her legs or keep her balance. There’s no more foxy lady, or cool Lady Day; no more R (rhythm) nor B (blues); she’s just a black-out drunk and drugged victim being urged on by a few cruel hecklers to humiliate herself a little bit more.

I could hear Jeremy singing in the bathroom.

Towering in shiny-metallic-purple-armor

Queen Jealousy, envy waits behind him

Her fiery-green gown sneers at the grassy ground

Blue are the life-giving waters

The once happy turquoise armies lay opposite ready

Then he came walking out of the bathroom, entirely naked, dripping wet with a towel in his hand, and belted out:

But they’re all bold as love …

Yeah, they’re all bold as love …

Yeah, they’re all bold as love …

Jeremy crawled into bed, picked up the Kinkell Castle book and started to read out loud a section describing a raid that might have once taken place on the castle: “The vaulted ground floor … was very strong and also fireproof—an important consideration when a flaming torch might be thrust through an arrow slit or gun loop.” Then the Ambien must have kicked in, because Jeremy was fast asleep and snoring.

So I popped one of Jeremy’s Adderalls, washed it down with a swig of whiskey straight from the bottle, and kept on typing. I knew I’d be up all night writing, and that by morning I’d have a text about the missing pop art painter Gerald Laing and his mysterious Amy Winehouse paintings to send to editor David and that other guy Donald, who’d had his bar mitzvah on the Allman Brothers tour bus.